William J. Ostiguy High School: A Safe, Sober Place for Teens

What is the first word that occurs to Dustin when he recalls his drug-addicted past at a public high school, interrupted by multiple stays at rehabs?

“Shame,” he says. “I knew I’d just been in a detox. They all knew it too. There wasn’t a lot of support. You’re just tossed back into the sea of people.”

That ended in 2015, when Dustin (not his real name), who by then was shooting heroin, was asked to leave his school. Today, he’s a Dean’s List junior at an area college with a GPA of 3.8, a major in psychology, multiple scholarships—and a limitless future.

Credit for this turnaround goes largely to Dustin. But save a bit for Boston’s William J. Ostiguy High School, one of about 45 recovery schools nationwide. Ostiguy is the 2018 recipient of Boston Children’s Hospital’s William L. Boyan Award, which annually honors a community organization, health center or school for its excellence in supporting the health and well-being of children and families in Boston.

Tough road for teens in recovery

According to the Department of Health and Human Services, approximately half of U.S. teens have misused prescription or illicit drugs at least once. And that’s not including the most abused drug of all: alcohol, which 58% of 12th graders drank in the past year.

Not all who consume these substances abuse them. But when teens do, and seek help, the odds are stacked against them in a traditional school setting. Roger Oser, who helped found Ostiguy and remains its principal, says research shows that after teens complete in-patient treatment, “once they go back to their schools, they relapse at a rate of 90%—in the first month.”

Located half a block from Boston Common, Ostiguy was launched in 2006 after its namesake, beloved Boston firefighter William J. “Willie” Ostiguy, learned how difficult it was for other firefighters’ teenagers who were battling addiction, no matter how determined they were. “I’m awestruck by the courage it takes for a young person to admit they have an issue,” Oser says. In seeking treatment, “You have to be humble. You’re doing something 99% of your peers aren’t doing.”

He adds that students in traditional high schools aren’t intentionally malicious—but we live in an age of intense, social media-driven peer pressure. To succeed, teens in recovery must “change up their people, places and things,” Oser says. Dr. Sharon Levy, Director of the Adolescent Substance Use and Addiction Program at Boston Children’s, agrees. “Places and [other] students are so triggering,” she says. “So a school that incorporates recovery into education is a godsend.”

About 75 students attend Ostiguy each year, making for enviably small class sizes and a feeling of community. “I’d been to 12-step meetings before,” Dustin says. “But I didn’t have a whole lot of hope.” That changed when he met other teenagers living in recovery; they modeled clean living for Dustin, and he notes with pride that “my ‘clean date’ is my date of enrollment at Ostiguy.”

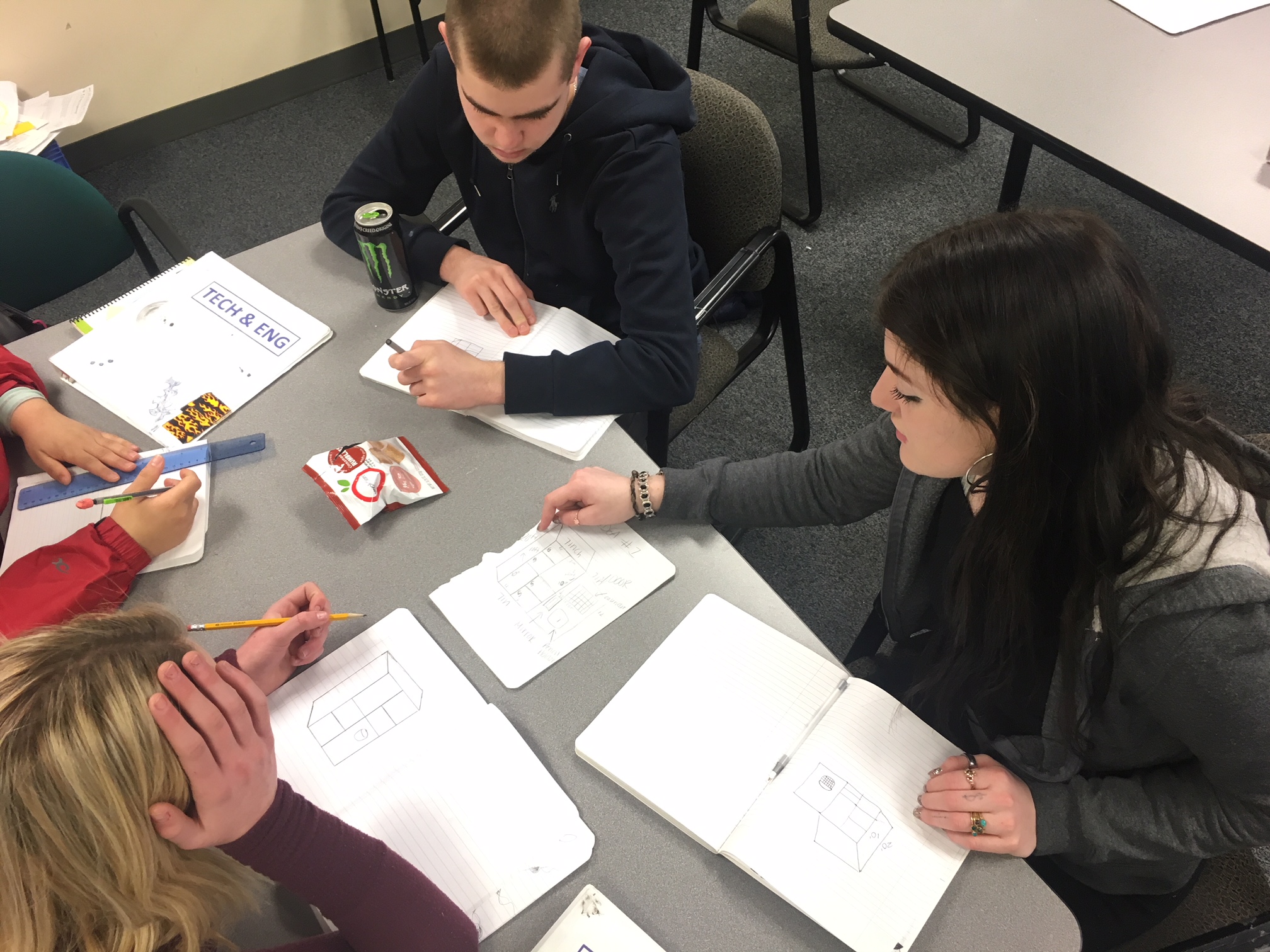

A typical day begins with a brief meeting of students, faculty and staff, setting the tone for the day. Then time for classwork, interspersed with varied healthy-living and sobriety-focused activities: yoga one day, a lecture on relapse prevention the next, art therapy the next. What Dustin most appreciated was the ever-present drug counselor, whom students are encouraged to visit whenever they feel the need.

Leading the way

Because recovery schools are new and rare, their statistical effectiveness is difficult to quantify. However, experts generally agree with a National Institutes of Health report that said, “these schools might be effective in reducing relapse to substance use and are simultaneously successful in helping their students succeed academically.” The success of schools like Ostiguy, combined with the opioid crisis, is spurring others to action. One recent summer day, Oser was preparing for a visit from a Los Angeles group curious to see what makes Ostiguy tick. That’s no surprise to Levy; “In my mind,” she says, “Ostiguy has a model program” when it comes to recovery schools.

The $50,000 that comes with the award will be put to good use: Oser plans to hire an intake specialist, freeing his time for outreach. “It’ll let me be out in the community,” he says, “making sure there’s awareness about the resources these students need.”

Surely that will lead to more success stories like Dustin’s. “The support from staff and teachers,” he says, “helped me get a better picture of what my life could be.”