Coarctation of the Aorta | Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of coarctation of the aorta?

In newborns, the onset of symptoms from a coarctation can be serious or even life-threatening. Signs of severe CoA in a newborn can include:

- Rapid breathing

- Pale or mottled skin

- Poor feeding

- Sweating or irritability

- Unresponsiveness

- Weak leg pulses

In other cases, a mild coarctation of the aorta may not be detected until a child is school-age, in adolescence, or even in adulthood. It is often spotted during a routine blood pressure test. As the child grows, signs and symptoms can appear, such as:

- High blood pressure

- Nosebleeds

- Heart murmur

- Headaches (from high blood pressure)

- Cramps in the lower sections of the body (from low blood pressure)

What causes coarctation of the aorta?

CoA may be caused by improper development of the aorta in the first eight weeks of fetal growth. But like other CHDs, it usually occurs by chance, with no clear reason for its development. It occurs in eight percent of children — and twice as frequently in boys — who have congenital heart disease. It also occurs in about 10 percent of girls who have Turner syndrome, a chromosomal abnormality.

Coarctation of the Aorta | Diagnosis & Treatments

How is coarctation of the aorta diagnosed?

Aortic coarctation can sometimes be detected during a prenatal ultrasound or a fetal echocardiogram. (Sometimes, though, the condition is hard to see in imaging.) If it is diagnosed in utero, once the child is born, they are typically brought to a cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) and placed on a prostaglandin infusion to keep ductal tissue from constricting. Using pictures from an echocardiogram, our clinicians consider a number of factors to decide whether the child needs a procedure to repair the coarctation or instead stop the prostaglandins and monitor the progression of the CoA. That monitoring is called an “arch watch.” Sometimes, coarctation is sufficiently mild and it can be simply monitored.

Other times, CoA is diagnosed or first detected after birth. In these instances, it can happen during a clinical exam, beginning with a child’s vital signs. One of our pediatric cardiologists will measure blood pressure in both arms and both legs. CoA may be suspected when the doctor notes lower blood pressure in the legs. The child’s leg or foot pulses will be weak and therefore difficult for the doctor to feel.

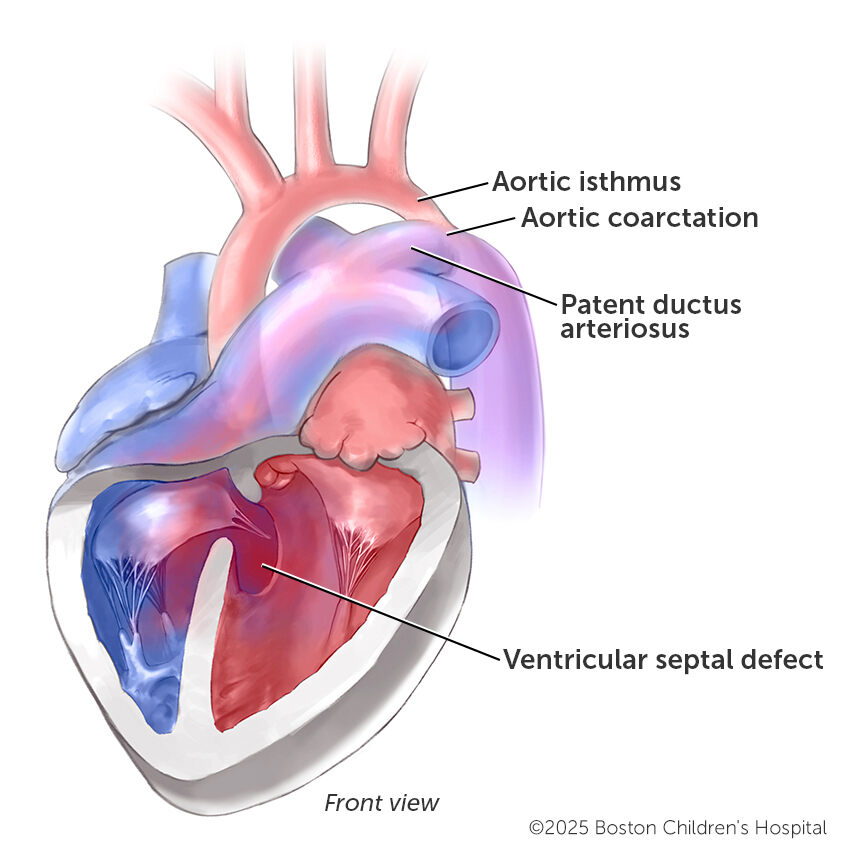

However, if the narrowing of the aorta is severe, a child will show serious signs and symptoms of CoA almost immediately after birth and the condition will be noticed. This happens with cases of CoA with a ventricular septal defect (VSD) or an interrupted aortic arch (IAA) with a VSD. In either of these cases, the natural closure of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) within the first days or weeks of life can be life threatening.

The PDA doesn’t close in some children, however, and can help distribute blood, but they are the minority of CoA patients. A drawback is the coarctation may be difficult to diagnose when the PDA is open, and sometimes it is necessary to repeat imaging while doing a trial off of a prostaglandin infusion.

Other tests that help with a diagnosis — or with planning for treatment — may include:

How we care for coarctation of the aorta

Our cardiac surgeons and cardiologists have vast experience treating infants and children who have coarctation of the aorta. The majority of coarctations are treated surgically, but some children are candidates for a less-invasive cardiac catheterization. Treatment plans are personalized to consider a child’s specific anatomy, age, size, and associated cardiac conditions.

How is CoA surgically treated?

Newborns who are very sick and require care in the CICU may need urgent repair of the coarctation. For most infants, a repair is done by our cardiac surgeons, who remove or patch the narrow part of the aorta. Depending on several factors, surgery may be performed from an incision on the side of the chest (a thoracotomy) and without cardiopulmonary bypass, or from the front of the chest (a sternotomy) with cardiopulmonary bypass. In either case, the goal is to remove the narrowed segment and sew the two healthy ends of the aorta back together, establishing normal blood flow through the artery.

To repair aortic coarctation, the narrow part of the aorta is removed and healthy vessel ends are joined — in what is called an end-to-end anastomosis. Also, the ductus arteriosus is ligated (tied off) or divided.

How is CoA with a VSD surgically treated?

If a child also has a large VSD, our cardiac surgeons sometimes repair that defect at the same time as the CoA. In other cases, a constricting band can be placed on the pulmonary artery to limit blood flow. If there's a bicuspid aortic valve (two valvular leafs instead of three), the aorta will need to be monitored by our cardiologists to make sure that blockage (stenosis) or leakage (regurgitation) does not develop later.

To repair aortic coarctation with ventricular septal defect, the narrow part of the aorta is removed and healthy vessel ends are joined to bypass the blocked segment — a procedure known as an extended end-to-end anastomosis. Also, the ductus arteriosus is ligated (tied off) or divided. A patch is applied to the VSD.

How is CoA with a narrowed aortic arch surgically treated?

Some patients also have narrowing of the aortic arch. Our cardiac surgeons may need to expand the arch and coarctation at the same time using a cardiopulmonary bypass. Depending on the anatomy, this repair can be achieved with all-natural tissue or a patch. In a small percentage of patients, the narrowing can return. In those small number of cases, a catheterization with balloon dilation is very effective. Rarely is a stent required.

How we are constantly improving CoA treatment

We’re always finding ways to improve how we treat children who have coarctation of the aorta. Whether it’s making a small adjustment or trying a new strategy, every innovation is supported by our experience and expertise. Here are some areas where we’ve advanced care for the condition:

- Achieving repairs without a heart-lung machine

- All-natural tissue repairs

- Advanced brain-protection strategies

- Minimally invasive and catheter-based solutions

- Collaborations between interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery