Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Shoulder Dislocation

What is a shoulder dislocation?

A shoulder dislocation happens when the ligaments that connect the arm to the shoulder are placed under so much force that the ball at the top of the arm bone separates from the shoulder socket.

Once a shoulder has been dislocated once, it will be prone to dislocate again in the future. If the nerves, blood vessels, tendons, and/or ligaments around the shoulder are damaged, the joint may require surgical repair.

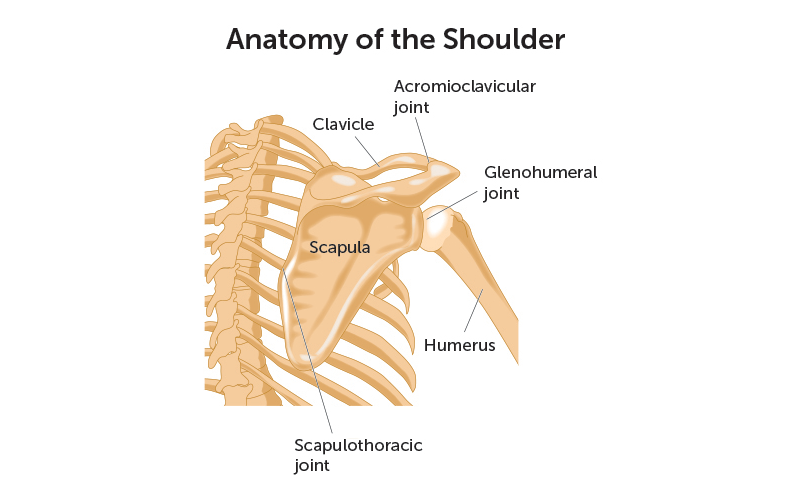

Shoulder anatomy

To better understand how a shoulder can dislocate, it helps to know about the anatomy of the shoulder. The shoulder is made up of:

- Humeral head: a ball at the top of the bone of the upper arm

- Glenoid: the shoulder socket in which the humeral head fits

- Scapula: the shoulder blade

- Labrum: a rim of cartilage that cushions the inside of the glenoid

- Joint capsule: a group of ligaments that connect the humeral head and glenoid

- Rotator cuff: muscles and tendons between the scapula and humerus that stabilize the shoulder joint

Symptoms & Causes

What causes a shoulder dislocation?

Shoulder dislocations are common in athletes who play contact sports, such as hockey and basketball, and sports in which athletes fall often, such as gymnastics and downhill skiing. Shoulder dislocations also often happen in car crashes and other accidents.

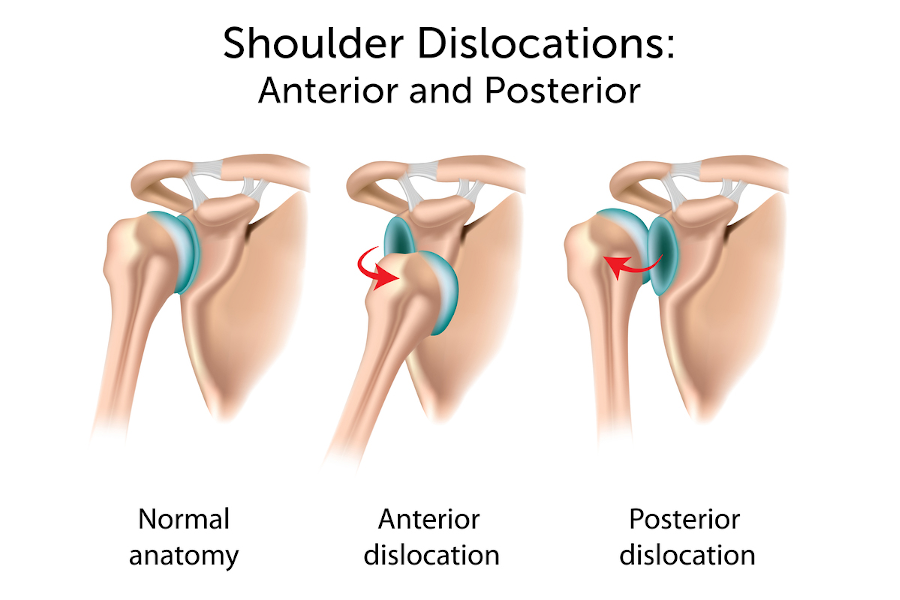

What are the types of shoulder dislocation?

Typically, the humeral head comes out of the glenoid when an arm is struck while being held out — like in the blocking position of a football linebacker. This type of dislocation, in which the ball of the humerus is forced forward, is called an anterior dislocation.

Occasionally, the humeral head can be pushed backward out of the glenoid due to a fall onto an outstretched hand or from a direct blow to the front of the shoulder. This type of dislocation is called a posterior dislocation.

Another type of shoulder dislocation can occur when one of the ligaments that attach the humeral head to the glenoid are torn or stretched.

Problems with the rotator cuff or the bones of the shoulder can also cause the shoulder to dislocate.

What are the symptoms of a shoulder dislocation?

- Extreme pain

- Inability to move the arm

- Numbness, weakness, or tingling around the neck or down the arm

- Painful muscle spasms around the shoulder

- A visibly deformed shoulder

- Swelling or bruising

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is a shoulder dislocation diagnosed?

A shoulder dislocation may resemble other conditions, such as a broken bone. If you suspect a shoulder dislocation, consult your child's doctor right away.

In addition to reviewing your child's full medical history and asking about events that may have caused the shoulder dislocation, your child's doctor may test:

- Movement and appearance of your child's shoulder muscles

- Pulse at the wrist

- Touch sensation

- Hand movement

They may also order one or more of the following tests to confirm whether you child’s shoulder is dislocated:

- X-ray: a test that produces images of internal tissues, bones, and organs

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): a test that produces detailed images of organs and structures within the body

- Radionuclide scans: nuclear scans of various organs to determine blood flow to the organs

- Electromyography (EMG): a test of the electrical signals in the muscles to determine the amount of muscle damage

How is a shoulder dislocation treated?

In most cases, your child's doctor can treat the shoulder dislocation without surgery. Your child’s treatment may include:

- Gentle movement of the arm to reset the bones in their original place (this may require a general anesthetic)

- Pain medication

- A sling or splint to stabilize and immobilize your child’s arm and shoulder

When is surgery necessary to treat a shoulder dislocation?

Typically, surgery is only considered after a conservative program of exercise has failed. If your child has had repeated shoulder dislocations, or if the shoulder instability affects their ability to use their arm, surgery may be an appropriate treatment.

The goal of surgery is to restore stability while maintaining mobility of the shoulder and providing pain-free range of motion.

- During the procedure, the surgeon will tighten any stretched ligaments or repair the labrum if it was torn at the time of injury.

- Some shoulder dislocations can be treated with arthroscopy, a minimally invasive surgical method of diagnosing and treating joint injuries through small incisions. But in many cases, open surgery is more effective in repairing shoulder instability.

- Typical success rates for open surgery for shoulder instability vary from 90 to 95 percent.

Is it possible to prevent a shoulder from dislocating again?

Your child may be able to compensate for loose ligaments by increasing the strength and control of their rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. These muscle groups help pull the humeral head into the glenoid and will pull more tightly if they are strong.

After a short period of immobilization with a sling, your child’s rehabilitation program may include:

- Exercises like closed grip pull downs, rowing on a machine, and shrugs, for shoulder blade strength

- Strengthening programs for the rotator cuff include rotation exercises with the arm down at the side

- Exercises that increase coordination of the shoulder using a medicine ball, and bouncing balls against the wall and the floor

How we care for shoulder dislocations

The experts in our Hand and Orthopedic Upper Extremity Program treat hundreds of children with shoulder dislocations and many other arm conditions each year. Because a dislocated shoulder is at risk for dislocating again, we help our patients strengthen the muscles around the shoulder joint to help prevent future injuries.

We regularly work with families to find the most conservative possible treatment for our patients’ shoulder injuries. If your child's injury is too severe for conservative approaches, we may recommend surgery to restore stability and range of motion to their shoulder.