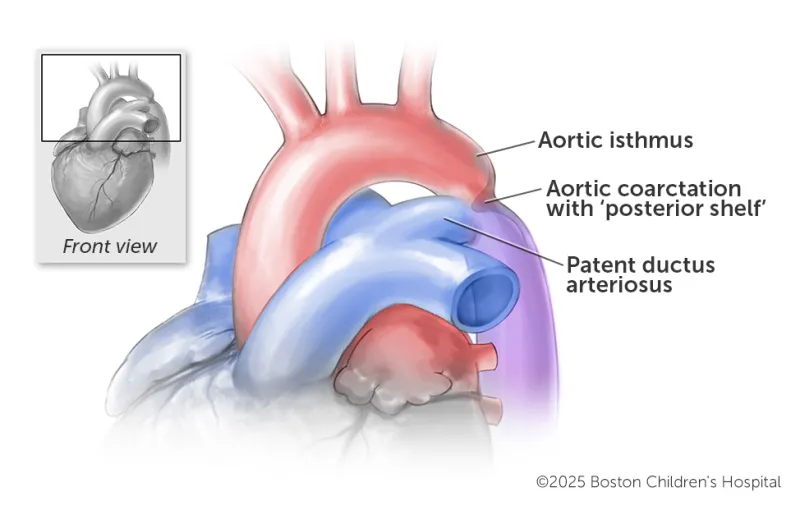

The aortic wall takes on a shelf form in the back, causing the aorta to narrow. If a prenatal artery called the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closes, as it naturally does in the first few days after birth, blood flow is further constricted.

Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Coarctation of The Aorta

What is coarctation of the aorta (CoA)?

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect (CHD) that causes significant blood flow constriction. If it is not diagnosed and treated, it can lead to high blood pressure and failure of the heart and other organs.

A CoA is a narrowing of the aorta, the main artery that delivers oxygen-rich (red) blood to the body. A coarctation is usually located just past the aortic arch, which has branches that deliver blood to the head and arms. When a child has CoA, their blood flow is restricted, making the left ventricle pump harder to push blood through the narrowed opening.

In severe cases, the blockage can cause the left ventricle to weaken and make a child very sick. CoA can be detected and diagnosed in utero (although it can sometimes be difficult to see in fetal imaging), and it can be diagnosed immediately after birth — both leading to quick treatment. But when it’s not detected until later in childhood, the blockage can cause the left ventricle to thicken and increase blood pressure in the brain. If the aortic muscle becomes too thick and is no longer able to function efficiently and handle its workload, it can eventually fail.

Coarctation of the aorta is a common CHD that can be treated through cardiac catheterization or cardiac surgery. Our specialists at Boston Children’s Benderson Family Heart Center have extensive experience diagnosing and treating the condition. Our outcomes show that the long-term outlook for children who are treated for CoA is excellent.

Which heart conditions are associated with CoA?

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

- Atrial septal defect (ASD)

- Aortic valve disease, usually in the form of a bicuspid aortic valve, when the valve has two valve flaps instead of three

- Aortic valve stenosis

- Mitral valve stenosis

- Patent ductus arteriosus

- Transposition of the great arteries (TGA)

- Double outlet right ventricle (DORV)

- Double inlet left ventricle (DILV)

- Single ventricle defects

What are the types of coarctation of the aorta?

Simple CoA

This type of CoA is like all other types of the condition in that the aorta is narrowed and constricting blood flow. It is considered “simple” because it is not associated with other heart defects. There are no holes in the heart as there would be when CoA is associated with an ASD or VSD.

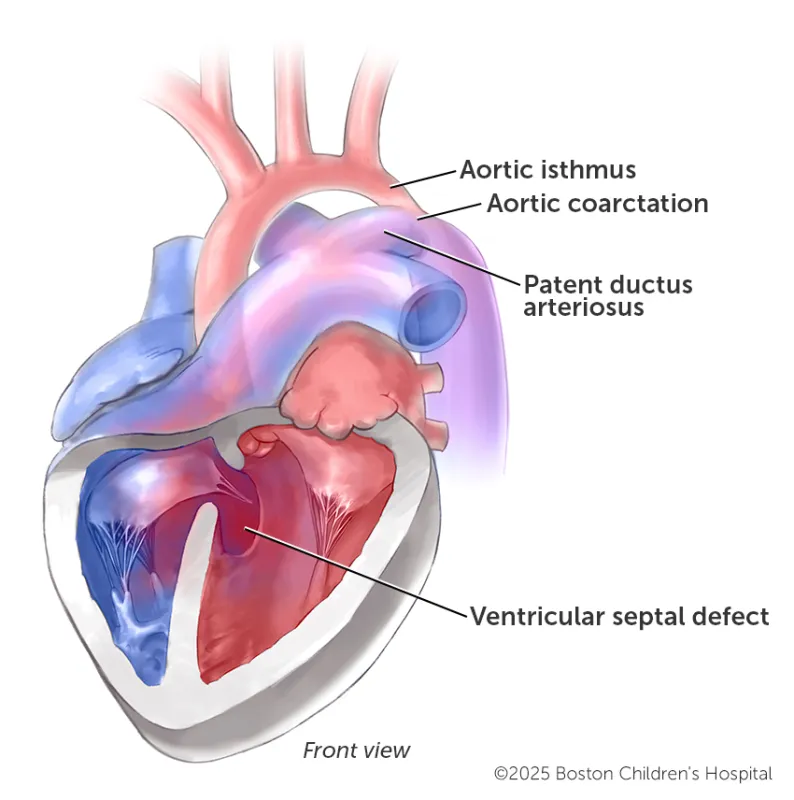

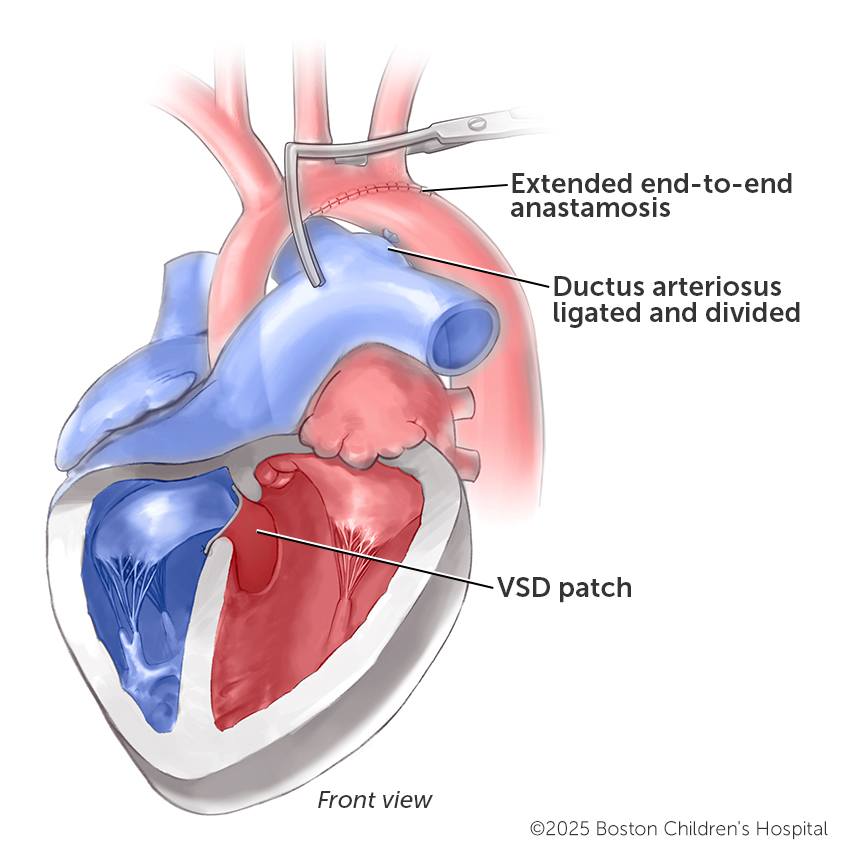

CoA with a VSD

With this combination of defects, there is blood flow blockage from the heart to the lower half of the body, and there is a hole between the ventricles, the two bottom chambers of the heart. Organs in the lower half of the body — including the kidneys, liver, and intestines — are affected by the impeded blood flow. If the PDA stays open, it can help deliver blood to those areas, but if it closes, blood flow is severely constricted.

A CoA with a VSD can constrict blood flow to the lower-half of the body because the aortic isthmus is usually narrowed or absent and the ventricular wall has a hole. As with other types of CoA, the patent ductus arteriosus could help blood flow if it stays open.

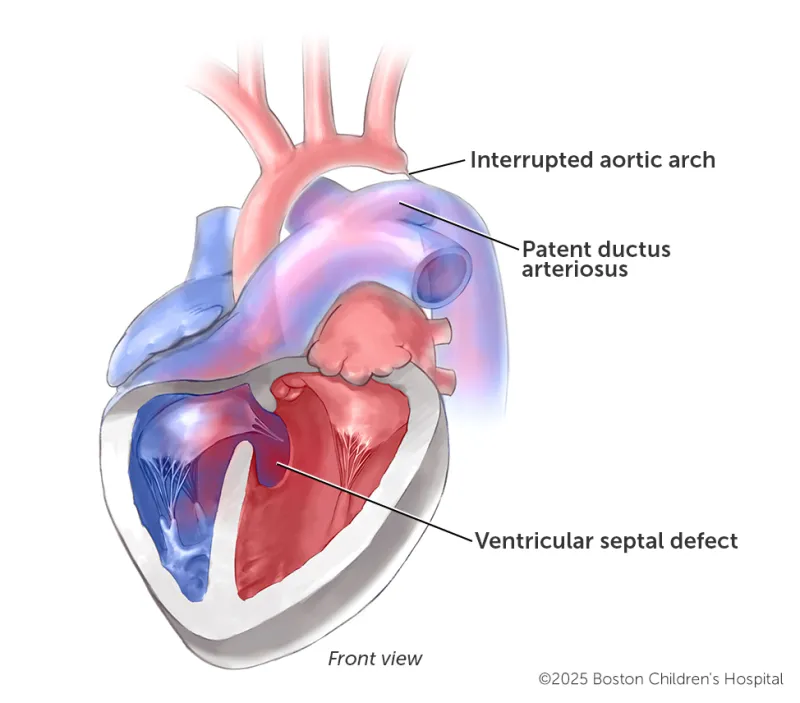

CoA with interrupted aortic arch (IAA) and a VSD

An interrupted aortic arch (IAA) is a rare CHD in which the aorta isn’t fully developed. With a missing section, or gap, in the arch, blood doesn’t reach the lower part of the body. The PDA can help by delivering that blood, but if it closes shortly after birth, lower-body organs are at risk from a lack of blood. Immediate surgery is necessary, as it would be if a child has CoA and IAA. Symptoms usually appear one to three days after birth.

Children who have a VSD and IAA experience limited blood flow to the lower body, and even more so if their PDA closes after birth.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of coarctation of the aorta?

In newborns, the onset of symptoms from a coarctation can be serious or even life-threatening. Signs of severe CoA in a newborn can include:

- Rapid breathing

- Pale or mottled skin

- Poor feeding

- Sweating or irritability

- Unresponsiveness

- Weak leg pulses

In other cases, a mild coarctation of the aorta may not be detected until a child is school-age, in adolescence, or even in adulthood. It is often spotted during a routine blood pressure test. As the child grows, signs and symptoms can appear, such as:

- High blood pressure

- Nosebleeds

- Heart murmur

- Headaches (from high blood pressure)

- Cramps in the lower sections of the body (from low blood pressure)

What causes coarctation of the aorta?

CoA may be caused by improper development of the aorta in the first eight weeks of fetal growth. But like other CHDs, it usually occurs by chance, with no clear reason for its development. It occurs in eight percent of children — and twice as frequently in boys — who have congenital heart disease. It also occurs in about 10 percent of girls who have Turner syndrome, a chromosomal abnormality.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is coarctation of the aorta diagnosed?

Aortic coarctation can sometimes be detected during a prenatal ultrasound or a fetal echocardiogram. (Sometimes, though, the condition is hard to see in imaging.) If it is diagnosed in utero, once the child is born, they are typically brought to a cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) and placed on a prostaglandin infusion to keep ductal tissue from constricting. Using pictures from an echocardiogram, our clinicians consider a number of factors to decide whether the child needs a procedure to repair the coarctation or instead stop the prostaglandins and monitor the progression of the CoA. That monitoring is called an “arch watch.” Sometimes, coarctation is sufficiently mild and it can be simply monitored.

Other times, CoA is diagnosed or first detected after birth. In these instances, it can happen during a clinical exam, beginning with a child’s vital signs. One of our pediatric cardiologists will measure blood pressure in both arms and both legs. CoA may be suspected when the doctor notes lower blood pressure in the legs. The child’s leg or foot pulses will be weak and therefore difficult for the doctor to feel.

However, if the narrowing of the aorta is severe, a child will show serious signs and symptoms of CoA almost immediately after birth and the condition will be noticed. This happens with cases of CoA with a ventricular septal defect (VSD) or an interrupted aortic arch (IAA) with a VSD. In either of these cases, the natural closure of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) within the first days or weeks of life can be life threatening.

The PDA doesn’t close in some children, however, and can help distribute blood, but they are the minority of CoA patients. A drawback is the coarctation may be difficult to diagnose when the PDA is open, and sometimes it is necessary to repeat imaging while doing a trial off of a prostaglandin infusion.

Other tests that help with a diagnosis — or with planning for treatment — may include:

How we care for coarctation of the aorta

Our cardiac surgeons and cardiologists have vast experience treating infants and children who have coarctation of the aorta. The majority of coarctations are treated surgically, but some children are candidates for a less-invasive cardiac catheterization. Treatment plans are personalized to consider a child’s specific anatomy, age, size, and associated cardiac conditions.

How is CoA surgically treated?

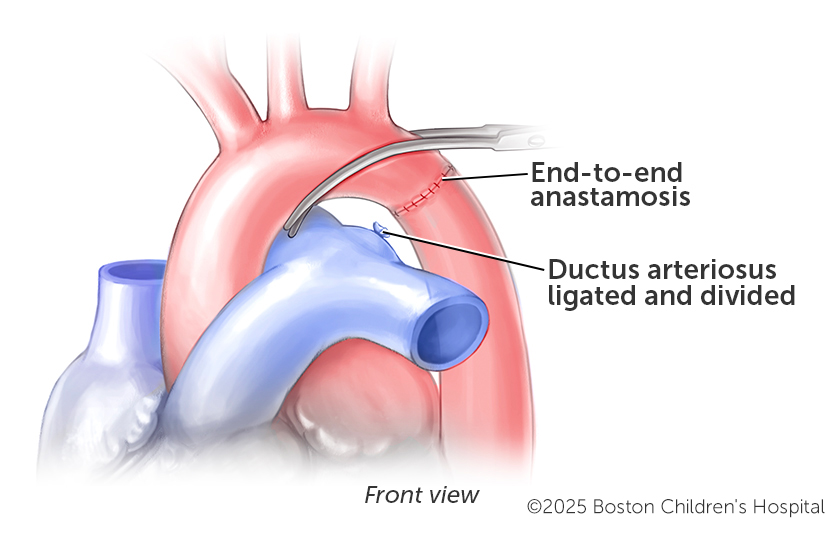

Newborns who are very sick and require care in the CICU may need urgent repair of the coarctation. For most infants, a repair is done by our cardiac surgeons, who remove or patch the narrow part of the aorta. Depending on several factors, surgery may be performed from an incision on the side of the chest (a thoracotomy) and without cardiopulmonary bypass, or from the front of the chest (a sternotomy) with cardiopulmonary bypass. In either case, the goal is to remove the narrowed segment and sew the two healthy ends of the aorta back together, establishing normal blood flow through the artery.

How is CoA with a VSD surgically treated?

If a child also has a large VSD, our cardiac surgeons sometimes repair that defect at the same time as the CoA. In other cases, a constricting band can be placed on the pulmonary artery to limit blood flow. If there's a bicuspid aortic valve (two valvular leafs instead of three), the aorta will need to be monitored by our cardiologists to make sure that blockage (stenosis) or leakage (regurgitation) does not develop later.

How is CoA with a narrowed aortic arch surgically treated?

Some patients also have narrowing of the aortic arch. Our cardiac surgeons may need to expand the arch and coarctation at the same time using a cardiopulmonary bypass. Depending on the anatomy, this repair can be achieved with all-natural tissue or a patch. In a small percentage of patients, the narrowing can return. In those small number of cases, a catheterization with balloon dilation is very effective. Rarely is a stent required.

How we are constantly improving CoA treatment

We’re always finding ways to improve how we treat children who have coarctation of the aorta. Whether it’s making a small adjustment or trying a new strategy, every innovation is supported by our experience and expertise. Here are some areas where we’ve advanced care for the condition:

- Achieving repairs without a heart-lung machine

- All-natural tissue repairs

- Advanced brain-protection strategies

- Minimally invasive and catheter-based solutions

- Collaborations between interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery