Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Pulmonary Atresia

What is pulmonary atresia?

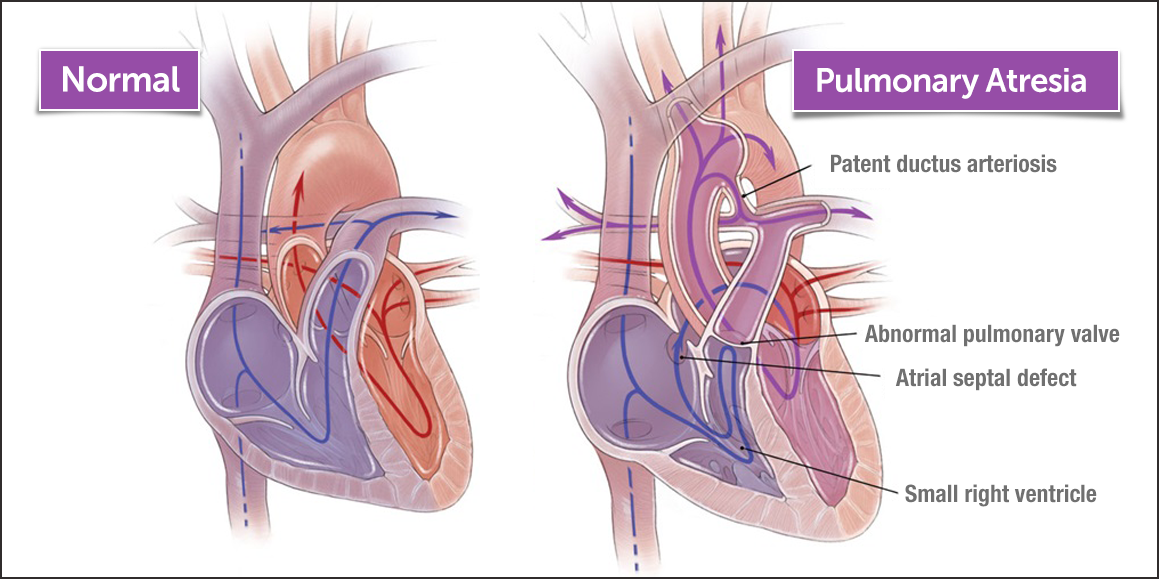

Pulmonary atresia is type of heart defect that a baby is born with. It occurs when the pulmonary valve — normally located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery — doesn’t form properly. This means that blood can’t flow from the heart to the lungs to get oxygen to the body. In some cases, babies with pulmonary atresia may also have a small, or missing, right ventricle that can’t properly pump blood to the lungs.

Pulmonary atresia is a life-threatening condition, affecting one out of every 10,000 newborns. Babies born with pulmonary atresia need medication and surgery to correct the heart defect and improve blood flow to the lungs.

How does pulmonary atresia look compared to a normal heart?

In a normal heart, blood enters the heart through the right atrium. From there, it flows through the right ventricle to the pulmonary artery and then into the lungs, where it receives oxygen. This oxygen-rich blood then returns to the heart via the left atrium, passes into the left ventricle, and is pumped through the aorta out, supplying the rest of the body with oxygen.

When a baby has pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve is not formed normally, so the blood cannot pass from the right ventricle into the lungs as it should.

What are the two forms of pulmonary atresia?

There are two main types of pulmonary atresia. The major difference is whether the baby also has a ventricular septal defect (VSD), which is a hole between the right and left ventricles.

- Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA/IVS): With this type of pulmonary atresia, there’s no VSD, so the right ventricle receives little blood flow before birth and can become small and underdeveloped. If the right ventricle is very small, it can’t perform its role as a pumping chamber. The coronary arteries, a type of blood vessel that provides fresh blood to the heart muscle, may not develop correctly. In these cases, the blood supply to the heart may be provided directly from the right ventricle through abnormal connections called coronary fistulas. It is important for your doctor to determine if the heart is dependent upon blood supply arising directly from the right ventricle.

- Pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect (PA with VSD): In this type of pulmonary atresia, the hole in the ventricular septum (VSD) allows blood to flow in and out of the right ventricle. This blood flow may help the right ventricle maintain size. PA with VSD is often related to another condition called tetralogy of Fallot. In those cases, it is referred to as tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of pulmonary atresia?

Symptoms of pulmonary atresia are noticeable shortly after a baby’s birth. The most obvious symptom is a bluish tint to the skin, called cyanosis. Other common symptoms include:

- Extreme tiredness

- Pale, cool or clammy skin

- Breathing problems

- Feeding problems

If your baby’s pediatrician notices any of these symptoms, he or she will order testing right away.

What causes pulmonary atresia?

There is no clear cause for this condition. When a baby has pulmonary atresia, the pulmonary valve simply doesn’t develop properly during the first weeks of heart development.

In some cases, congenital heart defects may have a genetic link, either due to a defect in a gene or a chromosome abnormality — causing heart problems to occur more often in certain families.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is pulmonary atresia diagnosed?

Most babies with pulmonary atresia are diagnosed shortly after birth. In some cases, it is diagnosed before birth by a prenatal ultrasound.

If your baby is born with a bluish tint to the skin or other symptoms of pulmonary atresia, he or she will likely see a cardiologist (heart doctor). Sometimes pulmonary atresia is first suspected during newborn screening, using pulse oximetry, a painless bedside test that uses a light probe, attached to the hand or foot, to detect the amount of oxygen in the blood.

To diagnose pulmonary atresia, the cardiologist will examine the baby and measure the oxygen level in his or her blood. The cardiologist will also listen for a heart murmur — a noise heard through a stethoscope that’s caused by the turbulence of blood flow. This will give the cardiologist an initial idea of the kind of heart problem your baby may have.

What tests will my child need?

The cardiologist may order one or more of the following tests to help diagnose pulmonary atresia:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

- Echocardiogram (cardiac ultrasound)

- Cardiac MRI

- Cardiac catheterization

- Chest X-ray

How is pulmonary atresia treated?

Babies with pulmonary atresia need some type of treatment soon after birth. The specific type of treatment your baby needs will depend on the severity of his or her condition. There are a few types of treatments for pulmonary atresia.

Medication

The doctor may give your child an IV (intravenous) medication called prostaglandin to keep the ductus arteriosus open. The ductus arteriosis is the connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery that is present in all babies before birth. This connection usually closes shortly after birth, but when kept open with medication, it can allow blood to continue to flow to the lungs until doctors decide on a long-term solution.

Cardiac catheterization

A cardiac catheterization is often performed to determine how blood is supplied to the heart in patients with pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum. Using this test, doctors can tell if the blood supply to the heart is dependent upon flow directly from the right ventricle through abnormal coronary connections, called fistulae. If the blood supply is dependent upon the right ventricle, surgery is recommended.

If the cardiac catheterization shows that the blood supply is not dependent upon the right ventricle, and the blockage is short, your doctor may recommend that the pulmonary valve is reopened in the catheterization laboratory, which involves crossing the pulmonary valve with a wire or a radiofrequency ablation catheter.

A special balloon can then be expanded in the middle of the valve to reestablish blood flow from the right ventricle to the lungs, allowing the right ventricle to grow over time. In many cases, it can allow for a biventricular repair and may reduce the number of surgeries. In some cases, it may eliminate the need for surgery altogether. If the pulmonary valve cannot be opened in the catheterization lab, then the connection between the right ventricle and lungs may be reestablished with surgery.

Surgery

Many children with pulmonary atresia need one or more surgeries to fix the problem. These surgeries may include:

- Right ventricular outflow reconstruction: This operation, often done shortly after birth, involves surgical reconstruction of a right ventricular outflow tract in order to allow blood to reach the lungs. Options for the reconstruction involve enlarging the connection from the right ventricle to the lungs with a patch or placement of a valved right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit. The goal of this procedure is to achieve a biventricular repair after one or two operations. Sometimes this procedure is combined with a Blalock-Taussig-Thomas (BTT) shunt.

- Blalock-Taussig-Thomas (BTT) shunt: This operation, done when the blood flow to the lungs is inadequate, is usually performed soon after birth to create a pathway for blood to reach the lungs. A connection is made between the first artery off the aorta and the right pulmonary artery. Some of the blood traveling through the aorta towards the body will “shunt” through this connection and flow into the pulmonary artery to receive oxygen.

- Bi-directional Glenn procedure: This operation, often done when a child is between 4 and 12 months old, replaces the BTT shunt (which the baby's heart will outgrow) with another connection to the pulmonary artery. During the procedure, a large vein (vena cava) that returns blood back to the heart is surgically connected to the pulmonary artery instead. This allows blood to move into the lungs to receive oxygen and can help the right ventricle grow.

- Fontan procedure: This operation, usually done in the first few years of life, is used when the right ventricle remains undeveloped, such as in severe forms of PA/IVS. This surgery directly connects returning blood from the lower body into the pulmonary arteries, bypassing the heart.

- Heart transplant: A careful evaluation is performed in order to decide if this is the best treatment option. Heart transplant is rarely needed for children with PA/IVS.

How we care for pulmonary atresia

The Benderson Family Heart Center at Boston Children’s Hospital treats some of the most complex pediatric heart conditions in the world. We provide families with a wealth of information, resources, programs and support — before, during and after your child’s treatment. With our compassionate, family-centered approach to expert treatment and care, your child is in the best possible hands.