Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Transposition of The Great Arteries

What is transposition of the great arteries (TGA)?

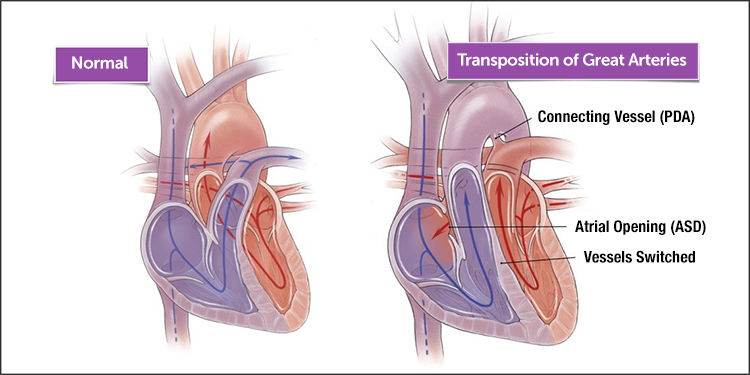

In transposition of the great arteries (TGA), the “great” arteries, the aorta and the right ventricle, are reversed in their origins from the heart. The aorta is connected to the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery is connected to the left ventricle — exactly the opposite of a normal heart’s anatomy. TGA is a universal term that may also be referred to as dextro-Transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA) and levo-transposition of the great arteries (l-TGA), otherwise known as congenitally corrected transposition of the greater arteries.

With these arteries reversed, oxygen-poor (blue) blood returns to the right atrium from the body, passes into the right ventricle, then goes into the aorta and back to the body. Oxygen-rich (red) blood returns to the left atrium from the lungs and passes into the left ventricle, which pumps it back to the lungs — the opposite of the way blood normally circulates.

Most babies with TGA are born with a small hole between their atria, which allows just enough red blood to get to the body to maintain life for a few hours. Typically diagnosed within the first hours after birth, TGA is life threatening, and in order to survive babies need special therapy urgently.

The most commonly used initial therapy is balloon atrial septostomy, where a balloon at the end of a catheter (small, flexible tube) is used to enlarge the opening between the atria. Complete open-heart repair generally takes place a few days later.

If there are no unusual risk factors, more than 98 percent of surgically-treated infants survive their infancy. Most children who’ve had TGA surgery recover and grow normally, although they can be at some risk in the future for arrhythmias, leaky valves and other heart issues.

What are other defects associated with transposition of the great arteries?

Most babies with TGA have only that defect, but there are other defects that can occur with TGA:

- Atrial septal defect (ASD): ASD is an opening between the right and left atria. This defect occurs occasionally with TGA and is actually helpful; it easily can be corrected at the time of surgery.

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD): VSD is an opening in the wall of tissue (ventricular septum) separating the right and left ventricles. This occurs in about 25 percent of patients with TGA. If large enough, a VSD will need to be surgically closed at the time of surgical correction.

- Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA): The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that’s normally open (patent) while the baby is inside the mother, but which closes naturally shortly after birth. Because keeping this vessel open helps increase the blood oxygen level in babies with TGA, doctors often give patients a medicine (prostaglandin E1) to keep the ductus open.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of transposition of the great arteries?

The symptoms of transposition of the great arteries may include:

- Cyanosis (blue coloration of the skin)

- Shortness of breath

- Lack of appetite

- Poor weight gain

What causes transposition of the great arteries?

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) is a congenital heart defect, which means children are born with it.

The heart forms during the first eight weeks of fetal development. The problems associated with TGA occur in the middle of these weeks, when the aorta and the pulmonary artery each attach to the incorrect heart chamber. It isn’t clear what causes congenital heart malformations, including TGA, although in most cases it appears that some combination of genetics and environment is involved.

Very few risk factors have been identified, but it appears that the risk of TGA is increased in mothers with type 1 diabetes mellitus (formerly known as "insulin-dependent" or "juvenile") and possibly with the ingestion of certain drugs, such as benzodiazepines.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is transposition of the great arteries diagnosed?

If, during pregnancy, a routine prenatal ultrasound or other signs raise suspicion of a congenital heart defect in the fetus, a cardiac ultrasound of the baby in uterowill usually be the next step. The cardiac ultrasound can usually detect transposition of the great arteries (TGA).

If your newborn baby was born with a bluish tint to his skin, or if your child is experiencing certain symptoms, your pediatrician will immediately refer you to a pediatric cardiologist, who will perform a physical exam. Your child’s doctor will listen to your baby’s heart and lungs, measure the oxygen level in his blood (non-invasively) and make other observations that help to determine the diagnosis.

For most patients, a echocardiogram (cardiac ultrasound) and chest X-ray is all that’s needed to form a diagnosis. But in certain circumstances, other tests may be necessary:

How is transposition of the great arteries treated?

After birth, a newborn with transposition of the great arteries (TGA) will be admitted to Boston Children's Hospital's cardiac intensive care unit (CICU). Initially, he or she may be placed on oxygen or a ventilator to help with breathing, and IV (intravenous) medications may be given to help the heart and lungs function more efficiently.

Once stabilized, the baby's treatments may include:

- Medication: Doctors may administer an IV (intravenous) medication (prostaglandin E1) to keep open the infant's ductus arteriosus (the prenatal connection between the aorta and the pulmonary artery, which usually closes shortly after birth, but which is now important as an alternative pathway for blood flow).

- Cardiac catheterization: Before TGA surgery, doctors may perform a cardiac catheterization procedure called balloon atrial septostomy to improve the mixing of oxygen-rich (red) blood and oxygen-poor (blue) blood. A special catheter with a balloon in the tip is used to create or enlarge an opening in the atrial septum (wall between the left and right atria).

- Surgery: Within a baby's first two weeks, transposition of the great arteries is surgically repaired through a procedure called an “arterial switch.” While supported by a heart-lung machine, the aorta and pulmonary arteries are disconnected, then “switched” and reconnected to their proper ventricles. As part of the procedure, the coronary arteries are transferred to the new aorta. In addition, any holes between the chambers of the heart are closed.

What is the long-term outlook for children with transposition of the great arteries?

The Benderson Family Heart Center team continues to refine their management of TGA and incorporate the latest innovations and research. Most children who've had TGA surgery recover and grow normally. Even so, your child will need periodic monitoring, since he or she may be at increased risk for arrhythmias, leaky valves, narrowing of the arteries and other heart issues.

How we care for transposition of the great arteries

At Boston Children’s Hospital, our team of experts in the Department of Cardiac Surgery has many decades of experience helping children who have been diagnosed with transposition of the great arteries.

Make an appointment

- Call us at 617-355-4278

- Email us at heart@childrens.harvard.edu

- Get a second opinion