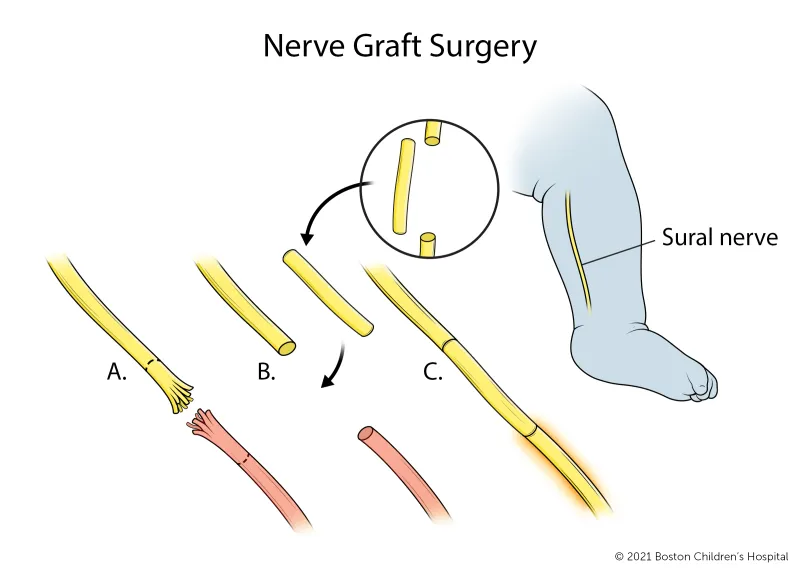

Nerve grafting surgery involves removing the injured portion of the nerve and replacing it with nerve grafts. These nerves usually come from the leg (sural nerves).

Breadcrumb

- Home

- Conditions & Treatments

- Brachial Plexus Birth Injury

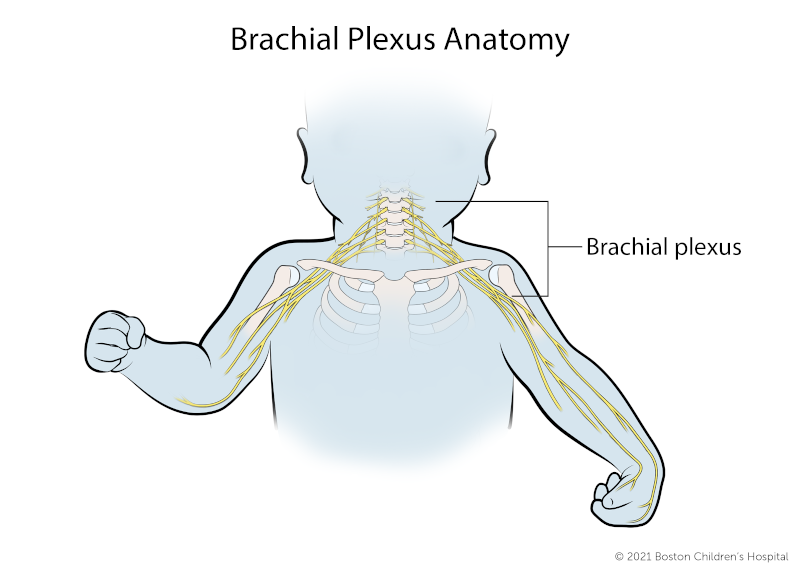

What is the brachial plexus?

The brachial plexus is a complex network of nerves between the neck and shoulders. These nerves control muscle function in the chest, shoulder, arms, and hands, as well as sensibility (feeling) in the upper limbs.

What is brachial plexus birth injury?

Brachial plexus birth injury, also known as brachial plexus injury, is an injury to the brachial plexus nerves that occurs in about one to three out of every 1,000 births.

The nerves of the brachial plexus may be stretched, compressed, or torn in a difficult delivery. The result might be a loss of muscle function, or even paralysis of the upper arm.

Injuries may affect all or only a part of the brachial plexus:

- Injuries to the upper brachial plexus (C5, C6) affect muscles of the shoulder and elbow.

- Injuries to the lower brachial plexus (C7, C8, and T1) can affect muscles of the forearm and hand.

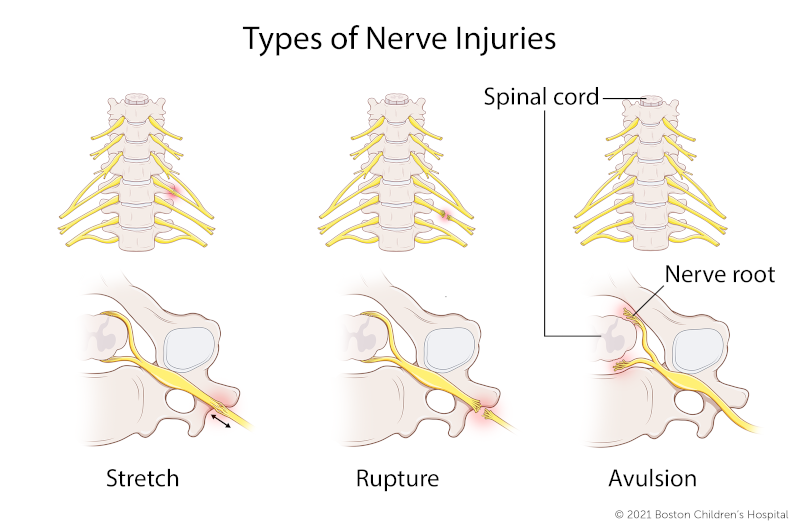

What are the types of brachial plexus injuries?

Brachial plexus birth injuries are often categorized according to the type of nerve injury and the pattern of nerves involved. There are different types of nerve injury.

Stretch (neurapraxia)

- Nerve has been stretched, but not torn

- Injury occurs outside the spinal cord

- Most common form

- Affected nerve(s) may recover on their own, usually within first three months of the baby’s life

Rupture

- Nerve is torn, but not where it attaches to the spine

- Injury occurs outside the spinal cord

- Common form

- May require surgical repair

Avulsion

- Nerve roots are torn from the spinal cord

- Injury occurs at the spinal cord

- Less common form (roughly 10 to 20 percent of cases)

- Cannot be surgically repaired directly — damaged tissue must be surgically replaced (nerve transfers)

- Can injure the nerve to the diaphragm, causing difficulty with breathing

- Droopy eyelid on the affected side may indicate a more severe injury, such as Horner’s syndrome

Erb’s palsy

It involves the upper portion (C5, C6, and sometimes C7) of the brachial plexus. A child typically has weakness involving the muscles of the shoulder and biceps. Home physical therapy begins when a baby is 3 weeks old to prevent stiffness, atrophy, and shoulder dislocation.

Total plexus involvement

This represents roughly 20 to 30 percent of brachial plexus injuries. All five nerves of the brachial plexus are involved (C5-T1). Children may not have any movement at the shoulder, arm, or hand.

Horner’s syndrome

This represents roughly 10 to 20 percent of injuries. It is usually associated with an avulsion. The sympathetic chain of nerves has been injured, usually in the T2 to T4 region. The child may have ptosis (drooping eyelid), miosis (smaller pupil of the eye), and anhydrosis (diminished sweat production in part of the face). The child may have a more severe injury of the brachial plexus.

Klumpke’s palsy

This almost never occurs in babies or children. It involves the lower roots (C8, T1) of the brachial plexus. It typically affects the muscles of the hand.

Symptoms & Causes

What are the symptoms of brachial plexus birth injury?

When a newborn has brachial plexus injury they may experience:

- Muscle weakness or paralysis in the affected arm or hand

- Decreased movement or sensation in the upper extremity

Usually, the baby is not in much pain, probably because infants’ nerves behave differently from adults’. Roughly, just 4 percent seem to experience severe pain. If a fracture accompanies the BPBP, the baby will experience some discomfort from the fracture, but not usually intense pain. And any fractures (clavicle, humerus) the baby may have will probably heal quickly — in about 10 days.

This is in contrast to an adult’s traumatic brachial plexus injury caused by accident or sports impact. In these cases, pain from brachial plexus injury is acute and disabling, as is pain from any accompanying fractures.

What causes brachial plexus birth injury?

The causes of brachial plexus injury may include:

- Large gestational size

- Breech birth

- Prolonged or difficult labor

- Vacuum- or forceps-assisted delivery

- Twin or multiple pregnancy

- History of a prior delivery resulting in brachial plexus birth injury

Once your child’s pediatrician has made a diagnosis, it’s safe to wait up to four weeks for a comprehensive evaluation by a pediatric orthopedist or brachial plexus specialist.

Diagnosis & Treatments

How is brachial plexus injury diagnosed?

Brachial plexus birth injury can be diagnosed by your baby’s pediatrician upon a thorough medical history and physical examination. Since the majority of babies with a brachial plexus injury recover in the first month to six weeks after they’re born, these exams can be scheduled with a primary care doctor. Children who continue to have problems beyond six weeks should be seen by a pediatric orthopedist or brachial plexus specialist.

In addition to a physical exam, doctors may conduct special imaging studies like an MRI or nerve conduction studies — although for babies, these tests are not as reliable as they are for adults. If doctors suspect that your child also has a fracture, they may take an X-ray, too. It’s important to find an experienced doctor who will be able to track your child’s progress over repeated exams.

How is brachial plexus injury treated?

Observation

Most brachial plexus injuries will heal on their own. Your doctor will monitor your child closely. Many children improve or recover by 3 to 12 months of age. During this time, ongoing exams should be performed to monitor progress.

Physical therapy or occupational therapy

Therapy is recommended to help maximize use of the affected arm and prevent tightening of the muscles and joints. With the teaching and guidance of therapists, parents learn how to perform range of motion (ROM) exercises at home with their child several times a day. These exercises are important to keep the joints and muscles moving as normally as possible.

What are the surgical options for brachial plexus injury?

Children who continue to have problems 3 to 6 months after birth may benefit from surgical treatment. Your child's doctors have several surgical options for treating brachial plexus birth injury, including:

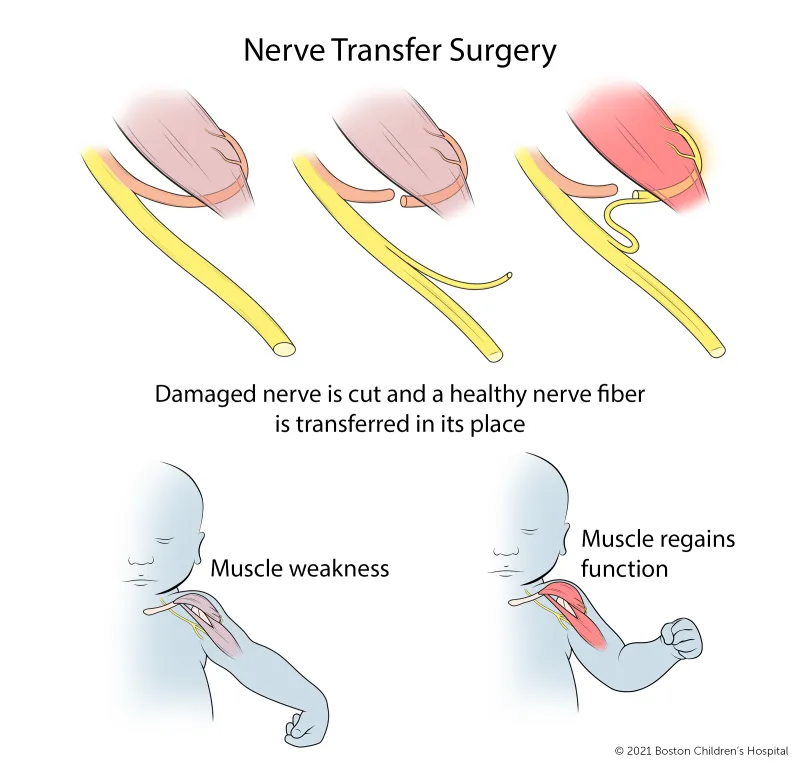

Nerve surgery

Nerve surgery, also known as microsurgery, repairs or reconstructs the injured nerves and is recommended if recovery is still inadequate 3 to 6 months after birth. This surgery generally consists of a combination of nerve grafting and nerve transfer procedures. It is best performed between 3 and 9 months of life and is usually not beneficial for children beyond 1 year of age.

Nerve transfer surgery redirects nearby nerves from the arm or chest to take over for the damaged nerves.

Osteotomy

An osteotomy is a procedure in which bones are cut and reoriented to improve upper extremity function by better positioning the hand and arm. It is most commonly performed on the humerus (upper arm bone) or forearm.

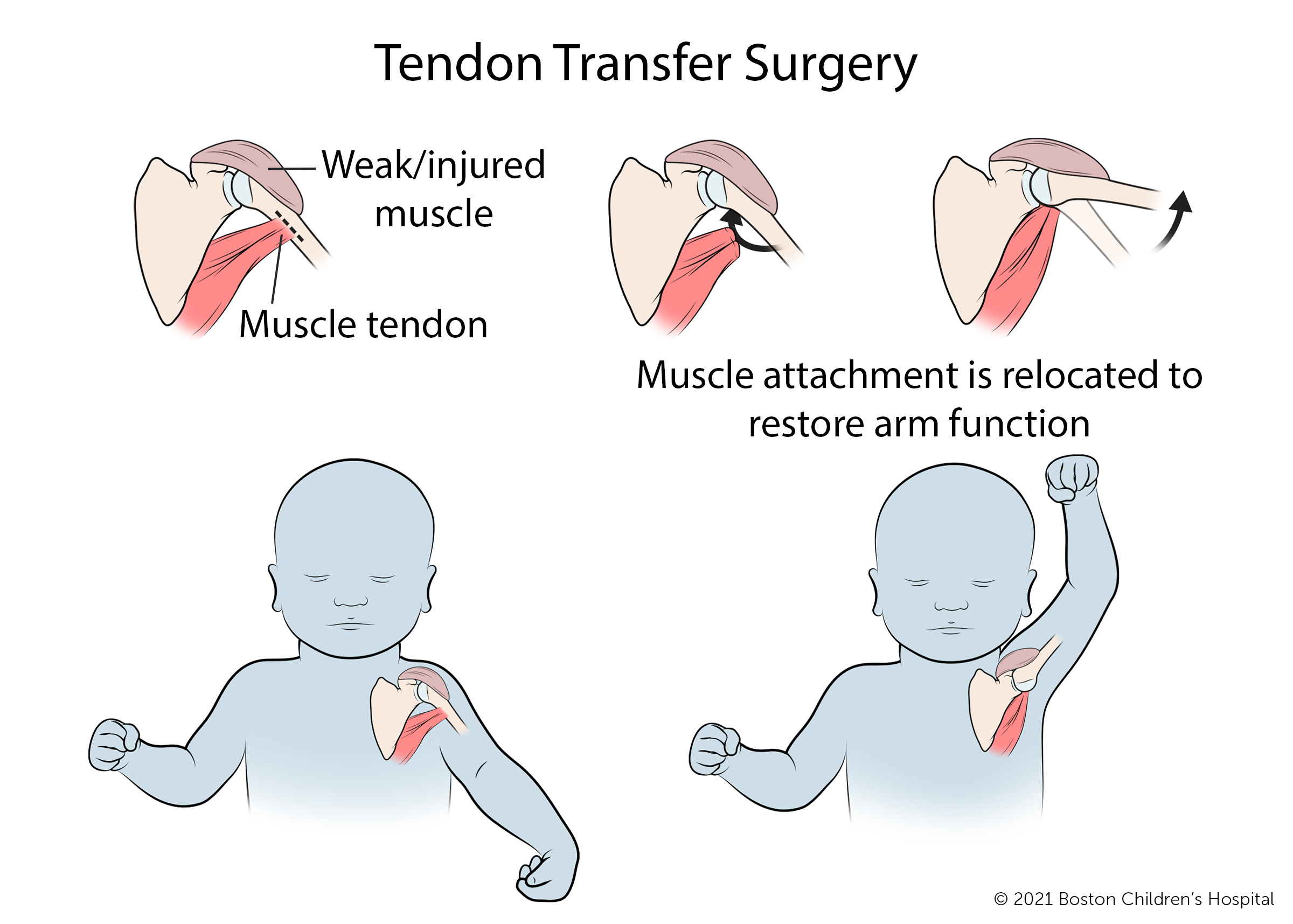

Tendon transfers

A tendon is the end of a muscle that attaches to the bone.

Tendon transfers involve separating the tendon from its normal attachment and reattaching it to a new location. This procedure, typically performed between age 1 and adulthood, allows a healthy muscle to help a weaker or injured muscle to return to its desired function. Tendon transfers are usually done around the shoulder to improve the ability to raise the arm, but may be done in the forearm, wrist, or hand. Children are often in a cast for four to six weeks after surgery.

Open reduction of the shoulder joint (capsulorraphy)

Open reduction of the shoulder joint, performed through a surgical incision or using arthroscopy, reduces (placing the humeral head back in joint) and surgically tightens loose tissue around the shoulder joint. The procedure is needed when persistent muscle weakness has caused shoulder joint instability or dislocation. It is often performed in conjunction with other surgical procedures.

Free muscle transfers

A free muscle transfer is an extensive surgery, typically using leg muscles, which required reconnection of blood vessels and nerves under microscope. It is performed only when there are no local muscles in the arm or hand to replace dysfunctional muscles.

What is the long-term outlook for brachial plexus birth injury?

This depends on the extend of the injury and varies from patient to patient. Most children develop normal, or near normal, arm function without surgery. But not all children recover fully. For these children, surgery can improve strength and motion and support healthy development of their shoulder joint.

How we care for brachial plexus injuries

As a national and international referral center for children with brachial plexus injury, the Brachial Plexus Program within the Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Department at Boston Children’s Hospital is among the largest in the world. The program has treated hundreds of babies and children — as well as adolescents, young adults, and even professional athletes who’ve sustained traumatic brachial plexus injury.

We’ve developed innovative non-surgical and surgical treatments for children with all degrees of severity of brachial plexus injuries. We can provide your child with expert diagnosis, treatment, and care — as well as the benefits of some of the leading clinical and scientific research.