Lyme Disease | Treatments & Prevention

How is Lyme disease diagnosed?

Most tests for Lyme disease look for antibodies the body makes in response to infection. Since it takes time for the immune system to produce these antibodies, an early test may come back negative, but your child could still have Lyme disease. Also, if your child has had Lyme disease in the past, the test may remain positive.

While currently available tests work in most cases, a clinical evaluation should take into account exposure to ticks, as well as the timing and nature of symptoms in making a diagnosis of Lyme disease.

Research is underway to develop and improve methods for diagnosing Lyme disease. Learn more.

How is Lyme disease treated?

Lyme disease is most often treated with antibiotics such as doxycycline, amoxicillin, or cefuroxime for several weeks. Please complete the full course of antibiotics as prescribed, even if your child is feeling better, in order to kill all the bacteria.

If your child doesn't respond to oral antibiotics, or if the Lyme disease is affecting the central nervous system, antibiotics may need to be given intravenously (through an IV). This usually doesn’t require your child to be hospitalized. In many cases, a nurse can come to your home to administer the IV or teach you or another family member how to do it.

Anti-inflammatory medicine may be prescribed for children who are experiencing pain from arthritis.

How can Lyme disease be prevented?

Unfortunately, there is currently no vaccine for Lyme disease. But you can avoid Lyme disease by avoiding tick bites, checking for ticks, and removing ticks promptly, before they become lodged in the skin. Some tips:

Avoid tick “playgrounds”: Ticks like low-level shrubs and grasses, particularly at the edges of wooded areas. If you’re hiking, try to stay in the center of the trail and avoid bushwhacking. Walk on cleared paths or pavement through wooded areas and fields when possible.

Dress appropriately: Long pants with legs tucked into socks and closed-toed shoes will help keep ticks away from skin. Light-colored clothing helps make ticks visible.

Insect repellant: Products that contain DEET repel ticks but do not kill them and are not 100 percent effective. Use a brand of insect repellent that is designated as child-safe if your child is 1 year or older. For infants, check with your pediatrician about what brands are safe to use. You can also treat clothing with a product that contains permethrin, which is known to kill ticks on contact.

Shower after outdoor activities are done for the day. It may take four to six hours for ticks to attach firmly to skin. Showering will help remove unattached ticks.

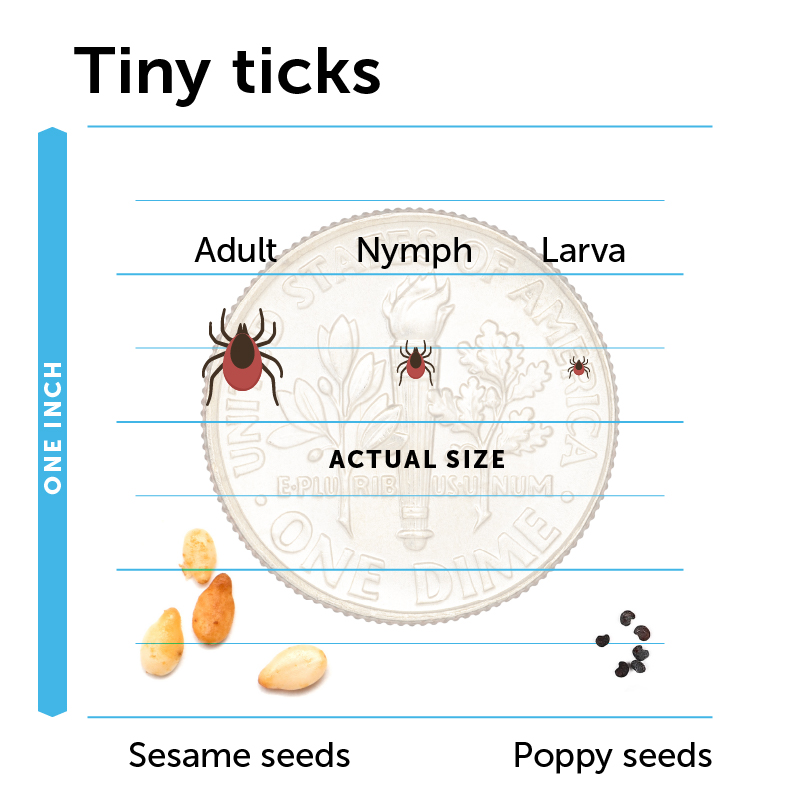

Check yourself and your family frequently for ticks, especially if you’re in an area where the ticks are common — even if you’ve only been out in your yard. Black-legged ticks can be extremely tiny, measuring less than one millimeter across, so make sure you search your child’s clothing and body very thoroughly. You or your child should perform one thorough tick check per day. Visually inspect all areas of the body including:

- all parts of the body that bend: behind the knees, between fingers and toes, underarms and groin

- other areas where ticks are commonly found: belly button, in and behind the ears, neck, hairline, and top of the head

- anywhere clothing presses on the skin

What should I do if I find a tick on my child?

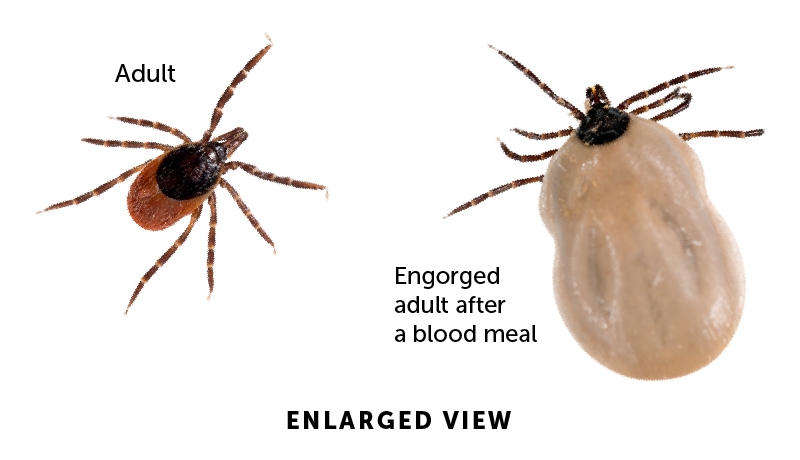

Don't panic. First Lyme disease is spread by the black-legged tick, not by the larger and more-common dog tick. The risk of developing Lyme disease after a black-legged tick bite is low, especially if the tick has been attached for a short time.

If you find a tick on your child, remove it using a fine-tipped pair of tweezers. Grasp the body of the tick and pull in an upward motion until the tick comes out. Do not squeeze or twist the tick’s body. Take note of the tick’s size and color, and how long you think it has been attached to your child.

If your child has been bitten by a black-legged tick that has been attached for more than 24 hours and you are in a Lyme disease endemic area, consult with your pediatrician. In some cases, your child may be prescribed antibiotics to prevent Lyme disease from developing.

Most children who develop Lyme disease do not recall having been bitten by a tick. Symptoms can appear a few days to many months after the bite, and can include:

Most children who develop Lyme disease do not recall having been bitten by a tick. Symptoms can appear a few days to many months after the bite, and can include: